22nd December 2023

Christopher Nosnibor

We live in strange times – times which have gone beyond the established expectations of what defines postmodernism into a period which is something else. Something else we’re yet to come to terms with, let alone define. Postmodernism heralded the arrival of what one might call ‘the nostalgia schtick’ by meshing together past, present, and future to conjure something of a liminal territory in which all times exist simultaneously. But if postmodernism, as defined by the likes of Francois Lyotard and Frederik Jameson is primarily defined by an accelerated pace of communication and an overwhelming blizzard of media, one thing which no critics or theorists could have readily anticipated when defining the term was the rush to cling to the recent past, or that the next big boom in industry would be nostalgia and revivalism.

The advent of the Internet heralded a revolution in terms of all things archival. Back in 1996 or thereabouts, when I first got online – with AOL on a floppy disc and a 14k dial-up modem plugged into a second-hand IBM 486 it seemed like a new dawn. It was basic, but text from obscure zines from the 60s, 70s, and 80s and pretty much anything you could ever wish for from the depths of the most subterranean archives was suddenly available, as was anything else. By the early 00s, Warren Ellis’ Crooked Little Vein was the world as it was: if it existed, it was on the Internet. But then the Internet got hijacked by big business, MySpace ceased to be the anarchic free virtual world that it had been, and everything turned to shit. Because capitalism ruins everything.

Amidst all of this, postmodernism is – or was – characterised by a celebration of depthlessness, of rejoicing in its own disposability, what Stewart Home referred to as ‘radical inauthenticity’. Postmodernism was laced with irony, knowingness, self-awareness. We seem to have lost the sense of irony and humourous knowingness somewhere along the way, and as we grapple with AI, deep fakes, and music industry plants, we have come to return to the question of authenticity as something which should perhaps be valued. Admittedly, these debates are perhaps minority issues, because for the most part society is split between those who believe everything they’re told and those who believe nothing, and there is only limited space for nuanced critical debate. It is, of course, hard to have a nuanced, critical debate in segments of 140 characters or so, and this compression, coupled with an ever-decreasing collective attention span has, undoubtedly been damaging in many ways.

The tug-o-war regarding the value of authenticity has been particularly apparent in music, as fellow musicians and critics alike have descended on punk and ‘indie’ bands to challenge their authenticity as exponents of punk and indie. With the rise of the ‘industry plant’ threatening the integrity of the DIY and indie music scene, it does make sense, but the point I suppose I’m ultimately making is that nothing really makes sense anymore, and that everything is a contradiction.

So, at the same time as AI has surged forwards to recalibrate the means of production, we’ve also witnessed a sustained boom in all things nostalgia. As much as it would pain many to admit it, it’s that same pining for the past that has driven the demand for vinyl, cassettes, grunge, tribute bands, as brought us Brexit. Admittedly, a yearning to return to the days of the Empire and when England resembled a Hovis advert is more socially damaging than basking in the glory days of Britpop, but it’s a pretty close call. A significant portion of the success of Stranger Things, for example, is its retro context, which has seen many hailing it as bearing parallels with The Goonies. I can’t help but wonder if this passion for the not-so-distant past is a means of escaping the absolutely hellish present and the utterly-fucked-up future we’re hurtling headlong into.

Conflux Coldwell’s latest project is one which plunges deep and direct into nostalgia, and as such resonates with the zeitgeist which has been simmering for a few years now. We’ve all seen it: the ersatz recreation of scratchy recordings, crackles and pops of old vinyl and the warps and snow of videotapes. And now everyone’s back to buying vinyl and audiotapes… how long before the VHS renaissance? And at the same time, it raises the question of ‘the archive’, of the (im)permanence of documents. We have always believed that documenting and recording events was the route to immortality, and that the advent of modern media would solidify our legacy in the same way as The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle or The Bayeux Tapestry. It was not so long ago that the Internet was supposed to be an eternal archive of everything ever. Only now, it’s apparent that modern technology is as ephemeral and disposable as our very culture, and that online archives vanish the moment their owners stop paying for the domain.

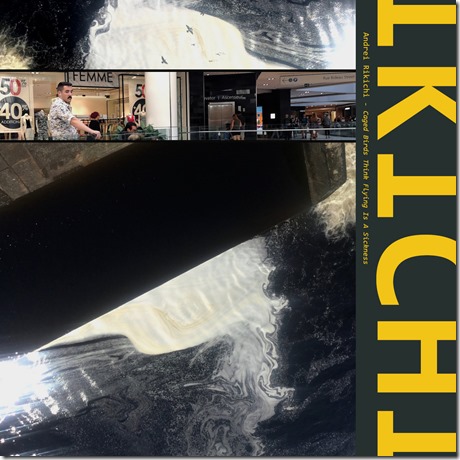

Memorex Mori is an unusually authentic work, born out of an excavation of -personal archives, as Coldwell explains: ‘Last year I found a dusty box of old unlabelled VHS tapes at my parent’s house, including some early work of my own I’d long forgotten about. Unfortunately the tapes were all in very poor condition and I only managed to recover some of the material. Despite the bad quality I decided to sample the videos anyway and make something new out of the various noisy remnants – the final result of that extended process is Memorex Mori.

Coldwell himself isn’t outside the frame of nostalgia with this ambitious project, either, as he continues: ‘VHS was the medium of my childhood in the 80s and 90s, and was still routinely used for budget productions by the time I started making films and music of my own. Looking through the old tapes made me realise the ultimate fragility of all our recordings and the memories they hold. These analogue tapes only have an estimated lifespan of 25 years, and this artificial life is only granted to the videos we actually decide to keep. The vast majority ended up in landfill when the world went digital – what was lost in the waste? In contrast, we might think that current digitisation and cloud storage allows our memories to live forever, but they are still fallible. The major difference is that with digital archives this mortality is hidden – with analogue media we can potentially witness that death happening in slow motion before our eyes.’

It’s an interesting and valid distinction between analogue and digital: growing up in the 80s and 90s myself, I remember being told not to vacuum clean near any video tapes, and so on, while toward the turn of the millennium the emerging digital future was presented as eternal. But now, it’s clear, that there is no such thing as permanence, or the eternal, and that any archive is as fragile as life itself.

And so, Memorex Mori is a multi-faceted, multi-dimensional, multi-media project, where past, present, and future collide, and postmodernism melts into the as-yet-to-be-defined present. It’s a film and it’s a soundtrack, and both can be appreciated independently of one another, as intended.

Coldwell expands on his notes, explaining ‘This project continues a lineage started by William Basinski and The Caretaker, exploring themes of memory loss, entropy and spectrality, through the sampling of destroyed recordings. But Memorex Mori extends this idea into the visual realm, presenting a feature-length music video alongside the music. As well as sampling early Conflux works from tape (Traveller, Glitch, Machinedance and Trainboy) various other unknown recordings were appropriated from the video box – all sorts of forgotten cultural detritus including my Mum’s 30 year old Open University programmes. A few modest pieces of equipment were used to add extra sonic layers – including the Korg NTS-1 and a home-made Marantz tape delay – then all bounced back to VHS.’

The video is a disorientating barrage of film clips, from train journeys to clouds, via small aircraft lifting off and droplets of water rippling out. Everything flickers and fades , glitches and warps. At times, we’re simply submerged in a snow of magnetic degradation and ruination, and it’s not always easy to discern what we’re actually being shown. But, often devoid of context, these detached, fragmentary scenes take on a sense of significance. The effect is an uncanny emotional response, a pull in the lower intestine as something unexplained and inexplicable evokes something within. There’s a comparison to be drawn with Memorex Mori and the experimental works created by William Burroughs and Brion Gysin in the late 50s and early 60s – in the soundtrack, the tape experiments, perhaps, but more so the whole audiovisual project, which calls to mind films such as Towers Open Fire, produced in the mid-60s with Anthony Balch, and a step closer to what Gysin’s quest to realise ‘a derangement of the senses’.

The soundtrack is the perfect soundtrack to this endlessly unsettling sequence, an eternally shifting sonic drift that’s at times noisy, even harsh, while at other altogether more ambient. Like the visuals, it draws you in, but it also stands independently as a purely sonic experience, and it’s also a smooth, expansive scene for reflection, and perhaps it’s to be expected that the soundtrack has greater impact when experienced in isolation, without the distraction of the visuals.

As a whole, or in part, Memorex Mori is quite an unsettling experience: visually compelling, and aurally challenging. It demonstrates the fragility of any documentation, any archive, and of life itself. Nothing lasts forever. And it speaks of how, as memory fades, so the documents diminish in value: moments captured in moving or still images which seem so essential at the time lose meaning over time: where was that picture taken? What was I doing there? Why did I think that would be worth filming / photographing? Who even is that?

I feel a weight descend as I reflect on all of these things while immersing myself in Memorex Mori. I can’t even begin to imagine the experience of assembling it. Then again, I can’t really assimilate the experience of other viewers or listeners, either. What’s intensely personal to an artist is likely to hit a spot with the audience, but for each, the reception will differ, based on their own experiences, their own immediate headspace.

But, regardless of individual interpretation, the vast ambition of Memorex Mori is matched by its accomplishment. THIS is a document. A powerful work, which will stay with you long after the silence descends.

AA