Sweden-based industrial/dark ambient artist ULVTHARM has released his second opus “7 Uthras” on May 3rd via Cyclic Law. The album is available as digisleeve CD (limited to 300 copies), black vinyl (limited to 200 copies), and red & black marbled vinyl (100 copies).

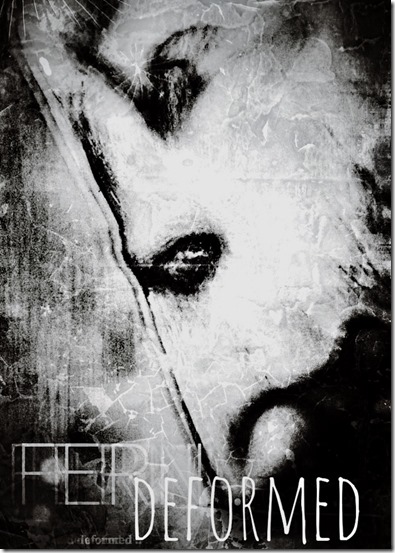

An official video has been released for the song ‘Sinners Will Inherit The Earth’. The video displays a female character – interpreted by the actress Emelina Rosenstielke (Feed) – sitting in a colorless room and in the center of a target painted on the floor. The character, who embodies modern civilization, is apparently afraid of the risks she may incur. Ulvtharm’s arrival on the scene and the subsequent initiation of a ritual reveal the true identity of the character, as well as of our civilization – thirsty for blood and personal success. We are all sinners on this Earth.

Watch it here:

“7 Uthras” is the second release from MZ 412 co-founder Jouni Ollila. Ulvtharm is painting his world as a sprawling, post-apocalyptic industrial wasteland, where humanity clings to survival in the shadows of monolithic factories and decaying cities. Skies choked with ash, and a sun that seldom breaks through the omnipresent smog. Within this landscape, the Seven Uthras exist not as beings of benevolence, but as ancient, god-like entities that emanate from the darkest depths of the earth, commanding forces beyond human comprehension. 7Uthras serves as a sonic gateway to otherworldly realms, offering a glimpse into the abyss that challenges and expands the listener’s perception of the known universe.

The artist masterfully blends the essence of dark industrial soundscapes with layers of mystical ambiance, creating an immersive experience that is both deeply unsettling and profoundly enlightening. This new album is not just an exploration of sound but a journey into the soul of its creator, exploring the chaos and darkness within his imagination. ULVTHARM’s deeper vocal experimentations are weaving a narrative that is both personal and universal. The album’s blend of dark, martial, pulsating rhythms and ambient organic soundscapes invites us to confront the death and ruins of our world. As each track unfolds, we will be drawn deeper into a narrative of chaos and transformation, where the end of one world signifies the birth of another. “7 Uthras” is not just an album; it is a ritualistic journey that seeks to unlock the ancient doors of perception and embrace the darkness as a path to enlightenment. All hail the Serpents, all hail the Seven Uthras!