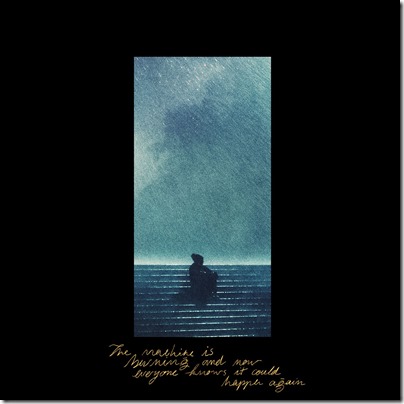

Dragon’s Eye Recordings – 23rd January 2026

Christopher Nosnibor

The facetious part of me reads the title of this as being a greeting to a pane of glass. I should probably get my coat after such a shameful revelation, but never mind. I’m here with my ears for this complex and detailed release, and will share the standard biographical info to provide much-needed context here:

‘Evening, window is the debut full-length album by Helsinki-based sound artist and ambient composer miska lamberg. Working with intricate field recordings that gather the overlooked moments of daily life – rainfall, distant traffic, animal calls – lamberg threads these textures into compositions that ache with personal memory. On Evening, window, the familiar becomes spectral: fragments of sound blur into melody and mood, capturing the stark melancholy of Nordic winters and the soft violence of remembering.’

The album features some long pieces: four of the six compositions are over eight minutes in duration, and this allows the pieces the appropriate and necessary time to build.

It begins with a metallic clattering. Heavy rain on a tin roof? Perhaps. Then there is a rumble – possibly thunder – but chattering abstract voices and soft, gentle synths drift in a cinematic spatiality and an organ swell gradually comes to dominate as it drifts… Evening, window is a sonic diary of sorts, a compilation of recordings captured in everyday settings as she goes about her life. The nine-minute opener, ‘Half-memories absorb us’ is both immersive and transportative, provoking contemplation. In some respects, the title does more than speak for itself, and also speaks of the way our minds work. And how do our minds work, exactly? Erratically, unpredictably, leaping from one place to another. And we’re thinking one thing while looking at another.

From a certain perspective, Evening, window can be seen to operate within the same field as William Burroughs’ cut-ups, and in particular the tape experiments he made with Iain Sommerville, although the collaging of field recordings and various layers of sound aren’t nearly as extreme here, blending the field recordings and decontextualised samples with carefully-crafted layers of ambience, which maked for a rather more listenable experience. Different objectives through similar intentions, one might say.

There are some haunting, unsettling motifs which cycle through Evening, window: ‘Seeing only faces turned away’ is dark, and listening to the ghostly swathes of ambience which hang dark and heavy is uncomfortable, a repetitive chord sequence conjuring, if not outright fear, then a sense of tremulous trepidation and unease. While Evening, window is a work of lightness and air, it’s also a work of slow, dense weight.

There are children’s’ voices. There are supple strings. At times, the atmosphere is soothing, sedative, but more often than not, there are undercurrents of tension, befitting of a dystopian thriller. Some may consider this to be something of a disconnect from the concept of presenting, or representing, fragments from the everyday life of the artist. But life is strange; the world is strange, and scary.

‘I remember the day the world lost color’ is bleak, barren, conveying the murky gloom of a blanket of fog, while ‘Its monotony is unrelenting’ is the drudgery of life – at least some periods of it – summarised in four words. Anyone who has endured a crap job will likely be able to relate to the sense that life is slipping by while days evaporate trudging through eternal sameness and feeling a sense of helplessness and a loss of identity, a distancing from the self. The sound is muffled, and very little happens over the course of eight minutes of crafted stultification during which the chord sequence of ‘Seeing only faces turned away’ is reprised, only slower, more vague, somehow tireder-sounding. It’s the soundtrack to hauling your living corpse through another dead, empty day – and another, and another, and another.

Evening, window isn’t depressing as such, but it is not light or breezy, and the mood is low and melancholy. It’s a slow, gradually unfurling work which drags heavy on the heart, an album which radiates reflection and low mood. It’s a dose of stark and sad realism, and an album which speaks so far beyond words.

AA